July 30, 2012

Only 2 days left of Daf Yomi

I’m down to the last 2 days of Daf Yomi and here’s something really interesting. Actually I finished the entire Tractate tonight rather than stop 2 pages short. The part I want to discuss in on Niddah 66a.

Those familiar with what the Orthodox call “family purity laws” know that a married couple must abstain from sex while the wife is menstruating and for seven clean/white days following, after which she immerses in a mikvah and is then permitted to her husband. Those familiar with Torah know that Leviticus 15:19 states: "A woman who has a discharge of blood from her body shall be a ‘niddah’ for seven days …” There is no mention of waiting for any clean days, so she immerses the evening of the eighth day.

To understand this contradiction, we turn to the Talmud, where the Rabbis’ discussions in Tractate Niddah clearly assume that women are supposed to immerse seven days after they become niddah. It is the zavah, the woman with an abnormal vaginal discharge lasting three days or longer, who must wait seven clean days before she immerses. How did these two get conflated?

The answer comes on page 66a, where R. Zeira says, “The daughters of Israel have imposed upon themselves the stringency that even where they see merely a drop of blood of the size of a mustard seed, they wait on account of it seven clean days.” Rava angrily replies, “I am speaking of a Biblical prohibition, and you talk of a custom?! Where the restriction has been adopted, it is accepted, and where the restriction has not been adopted, it is not accepted.”

Rava, who never loses a Talmudic argument to Rav Zeira, declares that the Law is as the Torah, and the Rabbis, say. Yet by the Middle Ages, Jewish Law had changed to conform to Zeira’s strict opinion. And how did this stringency arise? Scholars who study the Talmud in its Babylonian context see this as Jewish women’s ‘holier-than-thou’ response to Zoroastrian menstrual impurity laws, which forced a woman to separate from her family in a windowless hut for nine days.

July 28, 2012

Daf Yomi - Niddah pp. 64-65

Daf Yomi update – Niddah pp. 64-65. In only a few more days, the 12th Daf Yomi cycle will be complete and various celebrations will mark the event []. At this time, I’m not sure which ones I’ll attend, as the Orthodox view of women studying Talmud is problematic for me.

In the latest several pages I’ve studied, two at the beginning of Chapter Ten have long puzzled me. I discovered these years ago, when I began researching RASHI’S DAUGHTERS. The Mishna says: “If a young girl, whose menstruation has not begun, married, Bet Shammai ruled she is allowed four nights, and Bet Hillel ruled until the wound is healed … If she had observed a discharge while still in her father's house, Bet Shammai ruled she is allowed the initial marital intercourse only, and Bet Hillel ruled the entire first night.”

Clearly the Mishna is talking about virgins who bleed when their hymens are broken. The blood of virginity is pure, but the Rabbis are concerned lest she become niddah at the same time. So they make some fences to protect the couple from possible sin. Mishna seems to cry out for more explanation, especially as Jewish tradition requires a seven-day wedding celebration, yet it is difficult to imagine how happy this time will be if the couple must remain celibate.

The first question that came to my mind is how long the couple must wait until they can resume relations. The second is what other kind of restrictions, if any, are placed on the newlyweds during this time. Interestingly, the Gemara answers neither of these, although the discussion assumes that the couple must wait at least until she stops bleeding. One Babylonian rabbi is especially strict, saying that the man does not complete the act once her hymen is broken, but he is overruled [thankfully]. While these rules don’t appear to be for the brides benefit, it seems to me that allowing her time to heal can’t help but save her from potential pain and suffering.

July 23, 2012

Daf Yomi Niddah p. 61 - the story of Og

Daf Yomi update – Niddah p.61. After another week of differentiating bloodstains [menstrual vs. wound vs. louse vs. butchering animal], we come across something completely different on page 61a. Suddenly the discussion mentions a massacre that might have been avoided had Gedaliah heeded a warning against the killer. But Rava points out that the warning was lashon hara, evil speech - more commonly known as rumor or gossip - which we are not supposed to accept as true. However he then admits that a person should still be mindful of it, so as to protect oneself and others from possible harm.

The Gemara then gives an example of lashon hara that involved Moses fearing the mighty giant Og, King of Basham. This is followed by a piece of Midrash that explains Og’s fascinating history, illustrating how the Rabbis loved to fill in missing details about minor characters in the Torah.

We learn in Deuteronomy that Og was a giant whose bed measured 9 cubits by 4 cubits [a cubit is about 26 inches]. The Rabbis tell us that he was the grandson of the angel Shamchazai, who came down to Earth before the flood, intending to lead men away from their evil ways. Instead he was tempted by the beauty of women to marry and begat giant children. When the flood began, Og snuck into the ark, and when Noah discovered him, swore that if Noah saved him, he would be Noah’s slave forever.

Og kept his promise and was inherited by Noah’s descendents for ten generations, at which time he came into Abraham’s possession. Indeed, Abraham’s reliable slave Eliezer was none other than Og. And after Og/Eliezer performed the great service of finding Rebecca as wife for Isaac, Abraham freed Og in gratitude and gave him many riches. With his great size and wealth, Og made himself king of Basham, and every king of Basham after him was named ‘Og’ in his memory. Thus it wasn’t Eliezer/Og whom Moses killed but a different Og. Indeed, the original Eliezer/Og never died at all, but entered Heaven alive, like Elijah. Now wasn’t that an interesting story?

July 18, 2012

Promotion, promotion, promotion

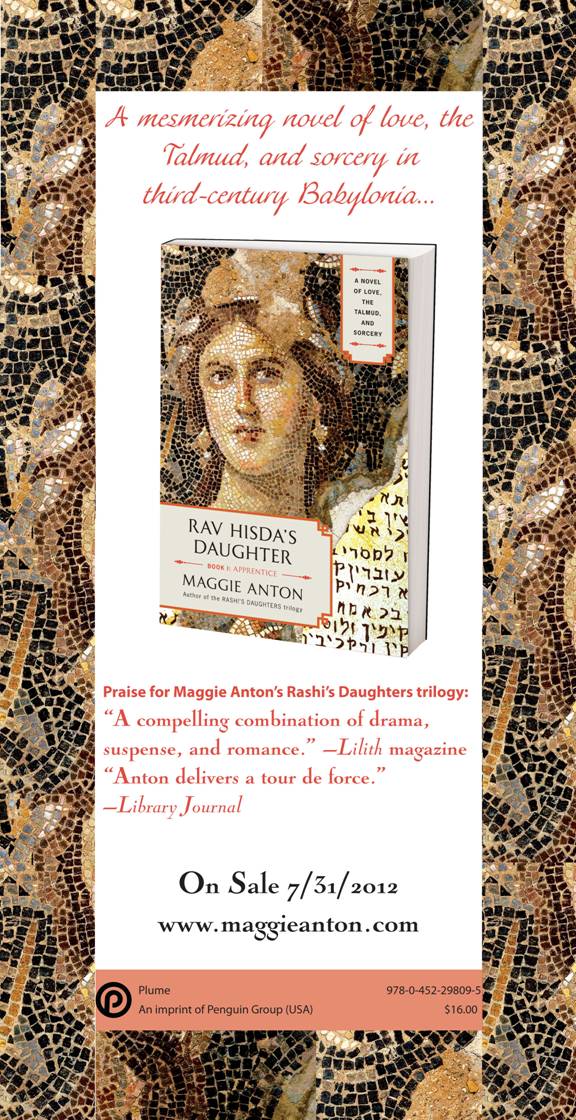

It is now just under two weeks before the publication date of my latest novel, RAV HISDA’S DAUGHTER, and I am trying to keep my head above water on the promotion front. Over the last ten days, I’ve been sending out an e-blast announcing my book’s imminent arrival to my 3300+ gmail contacts and yahoo group members. [What Yahoo group? Not a member? Join now].

This has been far more time consuming than I imagined, since I’ve never edited my gmail contacts before, and indeed, only recently learned where they are listed. As you could imagine, an unknown number of email addresses were no longer in service, and the only way to find out which was to send the eblast to everyone, see which ones bounced, and then delete them – a very time consuming process. Bottom line is that I now have 2800+ contacts where I used to have 3300.

Also time consuming, in a good way, was responding to the many replies my eblast generated. Some just wanted to say “Mazal Tov” or thank me for alerting them, but more than a few were speaking invitations, which necessitated opening the lengthy process of finding a mutually acceptable date. Thank goodness for my computer iCal, since I don’t even have a 2013 paper calendar yet. Among the replies were also requests for review copies, which I passed on to my publicist.

In between all this, there was my Daf Yomi to keep up, plus preparing the Reading Group Guide and author Q&A as well as coming up with descriptions of various lengths to describe the talks I’ll start giving next month.

No surprise that the last time I had time to write anything new for RAV HISDA’S DAUGHTER: BOOK 2 – ENCHANTRESS was July 8.

July 13, 2012

Internet problems and daf yomi

I must apologize for the week-long delay between posts. Just as I was embarking on an intensive campaign to alert my many email contacts, LinkedIn connections, and Facebook friends that RAV HISDA’S DAUGHTER is coming out on July 31, that is in a little over two weeks, my Internet service starting cutting out intermittently. To make matters worse, I had a Skype session with a synagogue in Tulsa interrupted five times before we gave up and continued via speakerphone. Yet despite my many complaints to TimeWarner, they were unable to schedule a service call until yesterday. The technician spent two hours testing various cables before tracing the problem to a faulty connection in the attic, which he replaced. Now all appears to be fixed, but I lost almost a week of time I would rather have spent doing something else, such as Daf Yomi. Since it’s almost Shabbat, I’ll share what I learned before this debacle happened.

Daf Yomi Niddah pp. 47-49. On page 47a the Talmud continues a lengthy discussion of how the Sages determine if a child has begun going through puberty, since the attaining of legal adulthood depends both on age and on physical maturity. Today we all know our birthday, and thus exactly how old we are. But not so in Talmudic times, despite the importance of knowing whether a girl is a child [eleven or younger], a naarah [in her twelfth year], or a bogeret [adult woman, older than twelve]. So the Sages looked to her body and describe, in detail that some might consider pornographic and others merely titillating [pardon the pun], the ways a girl’s breasts develops.

The Mishna states: “She is like budding fig while she is yet a child; a fig in its early ripening stage when she is in the age of naarah, a fully ripe fig as soon as she becomes a bogeret.” In case these metaphors are unclear, the Mishna continues with physical descriptions. “What are a bogeret’s signs? R. Yosi the Galilean says a wrinkle appears beneath the breast. R. Akiba says the breasts hang down. Ben Azzai says the areola darkens, and R. Yose says when one's hand pushes on the nipple so it sinks and delays rising.”

One can only imagine the unseemly thoughts that arose in the yeshiva students when the rabbis continued into the Gemara with further description of breasts, areolas, and nipples at each stage of development.

July 07, 2012

Daf Yomi - Niddah pp. 43-46

Daf Yomi Niddah pp. 44-46. In my last post I mentioned a "mokh," a tampon-like wad of wool or linen that women used to absorb their menstrual flow or, anointed with a spermicide, for contraception.

In Niddah 45a, we find one of three instances where the "Baraita of Three Women" occurs in the Talmud. Here's the text: " Rav Bibi recited before Rav Nachman: Three (types of) women use a mokh: a minor, a pregnant women, and a nursing mother. The minor, because she might become pregnant and die. A pregnant woman, because she might cause her fetus to become a sandal [flattened or crushed by a second pregnancy]. A nursing woman because she might have to wean her child prematurely and the child would die. These are the words of Rabbi Meir. The Sages say she cohabits as usual and Heaven will have mercy on her."

This Baraita has been the subject of much controversy, the question being whether Meir obligates these women to use a mokh while the Sages merely permit them or if Meir permits these women to use a mokh while the Sages prohibit them. Indeed, Rashi and his grandson Rabbenu Tam disagree on this, with Rashi taking the stricter interpretation that most women are forbidden to use contraception. Thankfully Jewish Law follows his grandson, and because only a man is commanded to procreate, Jewish women are free to use contraceptives if they wish. For more insights, see what the Jewish Women's Archive has to say on the subject.

July 04, 2012

Daf Yomi - Niddah pp. 41-43

Daf Yomi Niddah pp. 41-43. If I thought previous passages were complex, the Gemara adds a new discussion of how various types of impurity interact with each other, this time including impurity of nonkosher meat. Just when I thought my eyes were going to cross, I came across a short debate between Rava [hero of second volume of RAV HISDA'S DAUGHTER] and Abaye, his friend/study partner. Their apparently life-long relationship began when they were both children, studying with Abaye's uncle, and ended with Abaye's death as Rava adjudicates his widow's wine allowance.

There are hundreds and hundreds of arguments between Abaye and Rava, but the Gemara records only six where Abaye wins: Eruvim 15a, Gittin 34a, Kiddushin 51a, Sanhedrin 27a [twice], and Bava Metzia 21b. As for why Abaye continued to debate Rava when he almost always lost, you'll learn my opinion when you read BOOK TWO: ENCHANTRESS.

Interestingly, we have a debate between them on Niddah 24b that seems to end with Abaye winning. That is, Abaye's final point stands without Rava refuting it. The discussion resolves about the status of tumah/impurity of an item in a woman's vagina. Is it considered in a swallowed place and thus tahor because this is not carrying [Abaye]? Or it is considered in a concealed place and thus does impart impurity by carrying [Rava]? Generally the difference between swallowed and concealed is that the latter are places where the item can both be removed and partial seen, such as the ear and armpit.

But what about something in the vagina, where it cannot be seen but could be removed? While the Gemara doesn't give a definite answer here, I know from my research on RASHI'S DAUGHTERS, that Abaye did win. For when the medieval rabbis discussed a mokh inserted inside a woman to catch her menstrual flow, they said it was not considered carrying and thus was permitted on Shabbat.

July 01, 2012

Daf Yomi - Niddah pp. 37-40

Daf Yomi Niddah pp. 37-40. The Gemara now adds another type of impurity to the mix, one specific to women, tumat leidah, that of childbirth. The Torah [Vayikra 12:1-5] teaches that a woman who gives birth to a boy is tamei for seven days, followed by 33 tahor days during which time any vaginal bleeding does not render her impure. For a girl the mother is tamei for 14 days, and then tahor for 66. A unique element of childbirth is that it is not related to blood; even if there is no vaginal bleeding at all, the woman is nevertheless tamei.

I found two interesting passages in these pages the end Chapter Four and begin Chapter Five. The first, on pages 38ab, concern how long a pregnancy lasts. Most rabbis agree that labor can begin anytime during the ninth month, but the great Babylonian sage Shmuel, who knew a great deal about astronomy, says that a woman gives birth only after 271, 272 or 273 days. He even punished the husband of a woman who gave birth 269 days after she went to the mikvah, saying that he must have cohabited with her before, while she would still have been niddah. Apparently the anonymous "pious ones of old" would only cohabit from Wednesday through Friday so that their wives would not deliver a child on Shabbat and thus force its desecration for the sake of her and the child's health.

Then on page 40 we come across a rather amazing Mishna that says a baby born via Caesarean section [they don't call it that, but rather "one who exits through the wall" does not incur the standard periods of impurity and purity for its mother, nor does she offer the sacrifice for giving birth. Rabbi Shimon says that it is equivalent to a child born naturally. Of course we can tell from the name they had c-sections in ancient times, but everything else I've read about the subject indicates that the mother is already dead when the child is born this way. Here however, the rabbis are concerned about the rare [or imaginary] woman who is still alive when the surgery is performed and manages to survive it [].

And why not? They probably thought the Temple was more likely to be rebuilt than a woman would need to bring childbirth sacrifices after a c-section, but today it is the opposite. Thus the lengthy discussion that the Gemara discusses next, on the status of the children born "through the wall" and their mothers, turns out to have applications in Jewish Law today.